17 FASCINATING FACTS ABOUT ‘THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT’

Working with a miniscule budget of less than $25,000, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez wrote, directed, and edited one of the most successful independent movies ever made. It confused and frightened enough people when it was released in the summer of 1999 to earn more than $248 million in theaters worldwide. Twenty-five years later, it’s time to find out the truth about the Burkittsville, Maryland, legend.

The “script” for The Blair Witch Project was a 35-page outline.

Myrick and Sánchez wrote their first draft of The Blair Witch Project in 1993, when they were both film students in Orlando, Florida. They wrote the script more as an outline because they had always planned for the dialogue to be improvised by their actors in order to make the story seem real.

The audition process was unusual.

Actress Heather Donahue remembered reading an ad in Backstage that said: “An improvised feature film, shot in wooded location: it is going to be hell and most of you reading this probably shouldn’t come.” In order to test the improvisational skills of the candidates, as soon as each potential actor entered the room to audition, he or she was immediately told by one of the directors: “You’ve been in jail for the last nine years. We’re the parole board. Why should we let you go?’ If the actor hesitated for even a moment, the directors concluded the audition.

The three main actors were paid $1000 a day.

It was an eight-day shoot. Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard made a lot more in the years after The Blair Witch Project was released. Williams claimed he ended up with about $300,000.

Heather and Josh were supposed to be former lovers.

The idea was scrapped before shooting, though, ironically enough, a lot of tension did develop between the two actors/characters. When Heather called Josh “Mr. Punctuality,” it was an acidic in-joke (Leonard was very late that day). It was so “annoying” to the directors that they decided to kill off Josh first instead of Mike. Leonard was rewarded with a meal at Denny’s—the actors were only given rations of Power Bars and bananas while in the woods—and later a Jane’s Addiction concert while the other two remained at Seneca Creek State Park.

The teeth in the twigs were actual human teeth.

They were supplied by Eduardo Sánchez’s dentist. The hair was Josh’s real hair.

The actors used GPS trackers to find their instructions for the day.

Producers programmed wait points in the GPS unit for the actors to locate milk crates with three little plastic canisters in them. Each canister contained notes about where the story was going for each actor, who would not show the other two their paper. From that point they were free to improvise the dialogue, provided they followed the general instructions given to them. That left the actors to fill in their own blanks: “I wrote that whole piece in the cemetery—all those bits where my character's reading the narration for her documentary,” Donahue said. “I did research on all kinds of symbolic symbols, and Wicca, and how to stay alive in the woods. I did a very good job of freaking myself out as best I could before we even got there.”

The sounds of the children actually terrified Michael C. Williams.

Williams said the most terrifying moment was hearing the sounds of the kids that lived across the street from Eduardo Sánchez’s mother on three boomboxes being blared outside of his tent.

The actors had a code word for when they wanted to speak out of character.

“In the beginning, it was confusing, because we needed to set some boundaries as to when we were acting and when we were not,” Williams told The Week. “And the directors did not establish that for us; they wanted us in character as much as possible. So at one point we decided, as actors, that we needed code words to break from being an actor to being who we actually are.” They went with taco, which they each had to repeat “so I knew, and they knew, we were all out of character at the same time.”

It was too expensive to get the rights to some things.

In what would have been some fun foreshadowing, the directors wanted to have The Animals’ “We’ve Gotta Get Out Of This Place” playing on the car radio in the beginning of the film, but that was too pricey for the producers to keep. They did manage to get the rights for Heather to quote the theme to Gilligan’s Island, as well as approval to show their Power Bars.

Shooting finished on Halloween night.

The local Denny’s saw some extra business on October 31, 1997, as Donahue and Williams were also taken there for their first hearty meal in over a week. Williams described emerging from the woods and seeing people in costumes as “very surreal.”

Nineteen hours of footage was edited down to 90 minutes.

It took Sánchez and Myrick eight months to cut the movie for its Sundance premiere. Their initial cut was two and a half hours, and the scenes taken out of the theatrical version were used for the website and for the faux documentary that ran on Syfy.

Sánchez created the movie’s website himself.

The co-director was the logical choice to build the website that helped spread the myth of the Blair Witch to anybody wanting the information, as he was the only one involved with the movie who had website-building experience. According to Sánchez, he also had the free time available to work on the site as he didn’t have a girlfriend then.

The Blair Witch Project changed how movies were made and marketed.

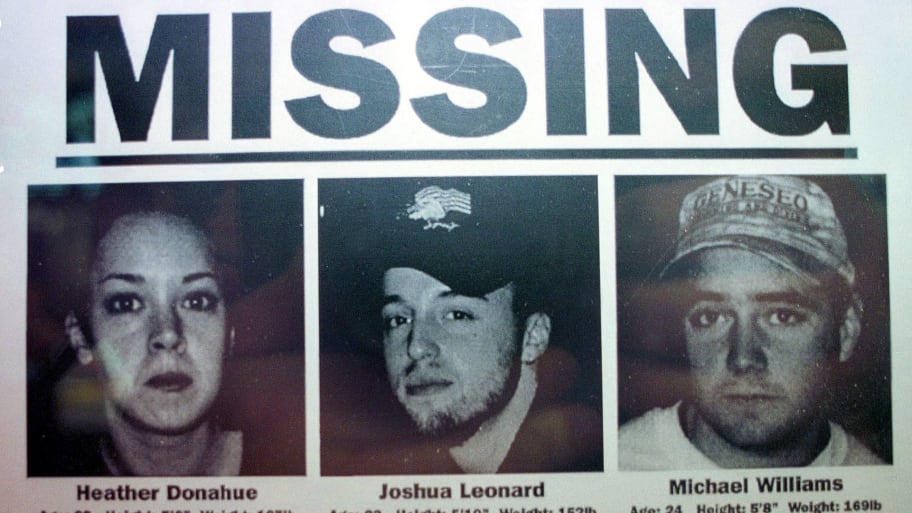

According to a 2019 article by Jake Kring-Schreifels in The New York Times, Sánchez’s website helped The Blair Witch Project go viral on the nascent internet a full year before the film’s release, thanks in part to the fact that it wasn’t presented as a website for a film at all. Artisan, the now-defunct studio that bought the rights to the film, also eschewed typical movie promotion by going to great lengths to keep Donahue, Leonard, and Williams away from the press for a time, and didn’t correct websites like IMDb that claimed the actors were deceased. By the time The Blair Witch Project hit theaters, many moviegoers thought it depicted real events. Donahue’s mother even received sympathy cards.

Ultimately, the film left a long legacy: Though it wasn’t the first found footage movie, “Its amateur aesthetic prompted a generation of filmmakers to pick up a camera, however low-tech,” Kring-Schreifels wrote. “It exposed new possibilities for marketing in the internet age. And it was a ubiquitous part of pop culture, spawning myriad imitators and spoofs, in turns inspired by and mocking its shaky cinematography and selfie-style confessionals. ... In some ways, The Blair Witch Project, with its blurring of fact and fiction, helped create that very media landscape that would preclude its viral success today.”

Some moviegoers got physically ill because of the shaky camerawork.

The regional director of Loews Cineplex Entertainment estimated that, on average, one person per screening got sick and asked for a refund.

Burkittsville, Maryland, has dealt with vandalism and creepy fans.

Burkittsville’s wooden welcome signs were stolen, as were their replacements. Artisan Entertainment bought the town four metal signs that have since rusted, or were also somehow stolen. Debby Burgoyne, the former mayor of the town—population: 150—once woke up to find a fan of the movie standing in her living room. He had apparently assumed there was a tour. “It was crazy,” Burgoyne told the Los Angeles Times. “People with cameras were everywhere. I made sure I had full makeup and a great nightie before I went out to get the morning paper.”

Only Leonard is still a full-time actor.

As of 2017, Donahue was working as a medical marijuana grower; she had also written a memoir, Growgirl. Williams quit his furniture mover job on Late Night with Conan O’Brien soon after The Blair Witch Project was released, only to return to it to supplement his acting income to support his wife and kids. Leonard is still acting.

There have been two sequels to The Blair Witch Project.

The 2000 sequel, Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, was considered a shameless cash grab that had little involvement from Sánchez and Myrick. The original co-directors talked about the possibility of a prequel set in the late 1700s, which hasn’t materialized. Adam Wingard (The Guest, You’re Next) directed a sequel, Blair Witch, that doesn’t acknowledge the events of Book of Shadows. A surprise trailer for the film (which had gone by the title The Woods) was dropped at San Diego Comic Con in 2016.

Read More About Horror Movies:

A version of this story ran in 2017; it has been updated for 2024.

This article was originally published on mentalfloss.com as 17 Fascinating Facts About ‘The Blair Witch Project’.

2024-07-01T21:26:53Z dg43tfdfdgfd